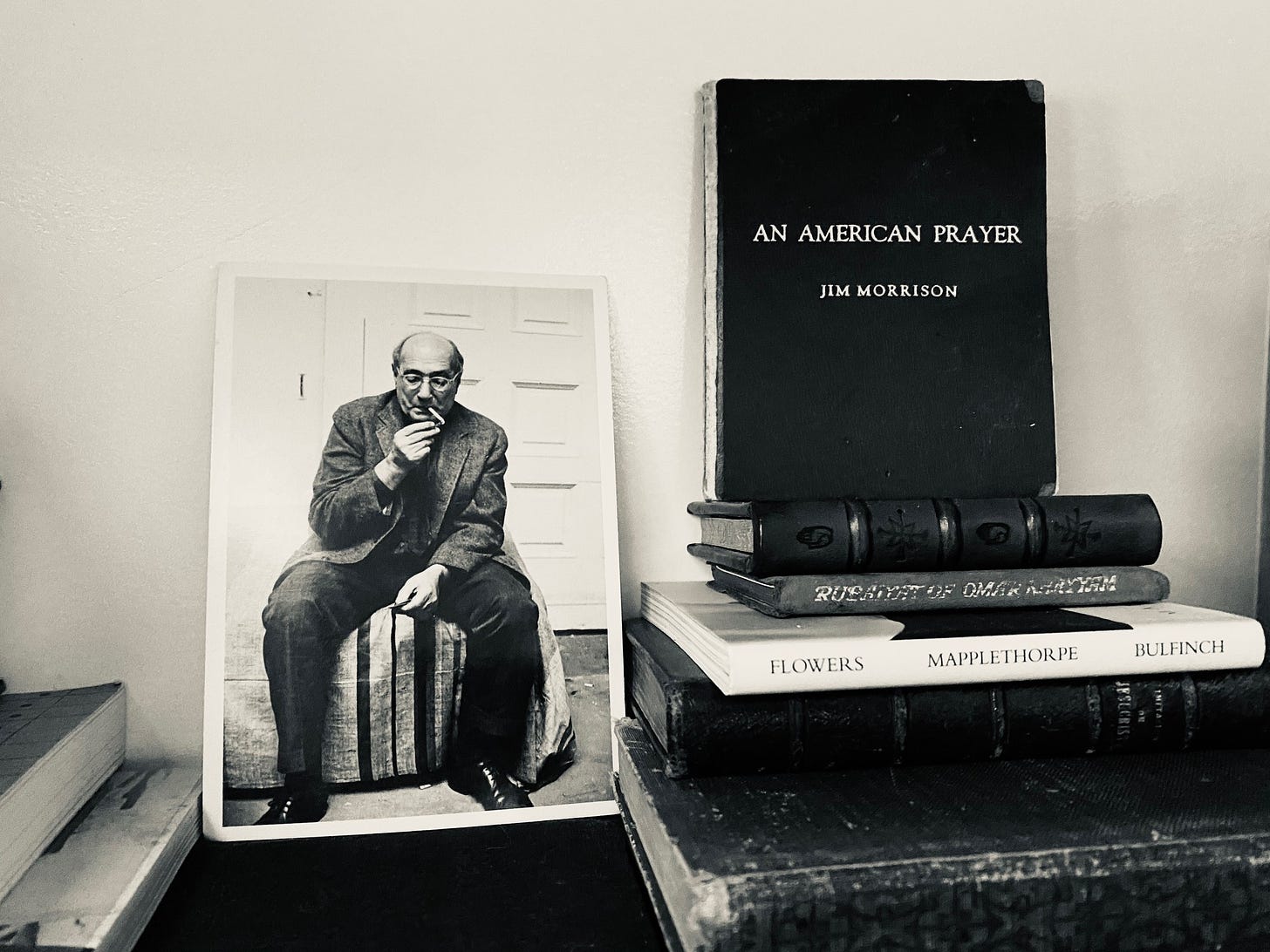

On my worktable is a postcard picture of Mark Rothko propped between small stacks of books. He is lighting a cigarette and for all the world looks like a man who knows who he is. I once saw him in an elevator in New York City in the fall of 1969. I was working at Scribner’s Bookstore, delivering books to a customer on the Upper West Side. I had chosen the books myself, works of Kerouac and Arthur Rimbaud, a birthday gift for a seventeen-year-old boy. I had performed the same task once before for a member of the Rothschild family, a friend of Mr. Scribner. I remember that Mr. Rothschild was wearing a black cashmere overcoat and carrying a black umbrella, although it wasn’t raining. He asked me to select books for his impossible to please nephew. I was twenty-two at the time and certainly up for the challenge, gathering a pile of works of subversive beauty. His nephew was so delighted with his gift that I became the designated shopper for relatives of restless young men.

I was holding my parcel when Mark Rothko got into the elevator. He was wearing dark tweed, standing there next to the panel of buttons. At first neither of us pushed a button, then we simultaneously reached out. The elevator was kind of slow. I wanted to say something but all I could muster was something like “nice coat.” He sort of smiled then got off on the floor before me and that was that.

There was a party going on. I handed over the books and was given a five dollar tip, which was great, although Mr. Rothschild had given me a fifty-dollar bill for my efforts and a handwritten note on a French carte d’visite. As I rode down the elevator I speculated as to which apartment Rothko had gone into. I wondered if I waited long enough if I might see him leave the building. I thought about it but it was getting cold. And what would I do if he exited? Most likely hide my face, for who would want to bother such a man?

The following February, Mark Rothko was found dead in his studio. He had slit his wrists with a razor and bled out, a phrase you mostly hear on detective shows—the victim was left to die in an alley and bled out. It was not very cold on the day he died, an unseasonably fair Wednesday, the child’s day of woe. But in the morning, heading to work, it was freezing. My coat wasn’t heavy enough and I had no scarf. It was at that moment, shivering as I crossed 5th Avenue, that I started obsessing about Rothko’s coat. I thought back to that afternoon in the elevator and his tweed coat that seemed so perfectly him, and wondered what became of it. Was it hanging on a hook, draped over a chair, had anyone noticed it and if so, what was its fate? Perhaps the assistant who found him happened upon it, and rescued it from future abandonment. I envisioned it dutifully folded, wrapped in tissue, then laid in a large box and set away like Proust’s overcoat, stored somewhere outside Paris. Mark Rothko’s coat. I fretted over it so much that I felt I should have it, for I was sure no one would cherish it as much as me.

At the time, I had a grey London Fog with a wool lining that I had gotten at the sprawling Goodwill in Camden, New Jersey. It was a classic, though a bit worn and had cost me five dollars, which was an investment in 1967. I adored it, a man’s heavy grey raincoat, evoking the weather of the Lake District in the country of poets. It felt like a part of who I was. I slept in it, wore it in all seasons, through times of adventure and want. And yet I inexplicably shed it, leaving it one warm afternoon on a coat rack in an empty office in the Flatiron Building in New York City.

Recommended: About Rothko by Dore Ashton | Artists 1950-81 by Hans Namuth

Thank you all for your comments. I read them all as no one has read The Melting and these are my first and most meaningful reviews.

I wonder if anyone has ever told you what a fine writer you are. xo